The notion that exercise is beneficial for overall health is widely accepted, but can physical activity go as far as to directly inhibit cancer cell growth? Emerging scientific evidence suggests a compelling link, indicating that regular physical activity can indeed play a significant role in both preventing cancer and slowing its progression at a cellular level. From altering the body’s metabolic landscape to boosting immune function and directly impacting tumor biology, exercise is increasingly recognized as a powerful, non-pharmacological intervention in the fight against cancer.

The Scientific Basis: How Exercise Influences Cancer Biology

Research has unveiled several intricate molecular and physiological mechanisms through which exercise exerts its anti-cancer effects. These mechanisms often work in concert, creating an environment less conducive to cancer cell proliferation and survival.

Modulating the Immune System’s Anti-Cancer Response

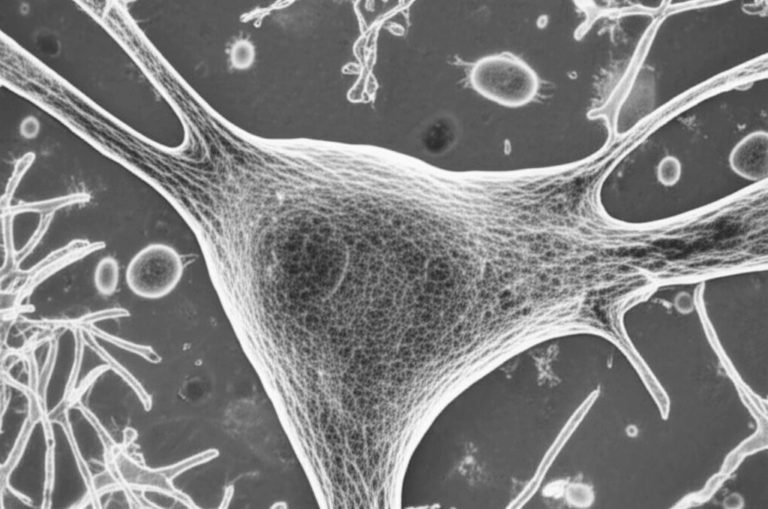

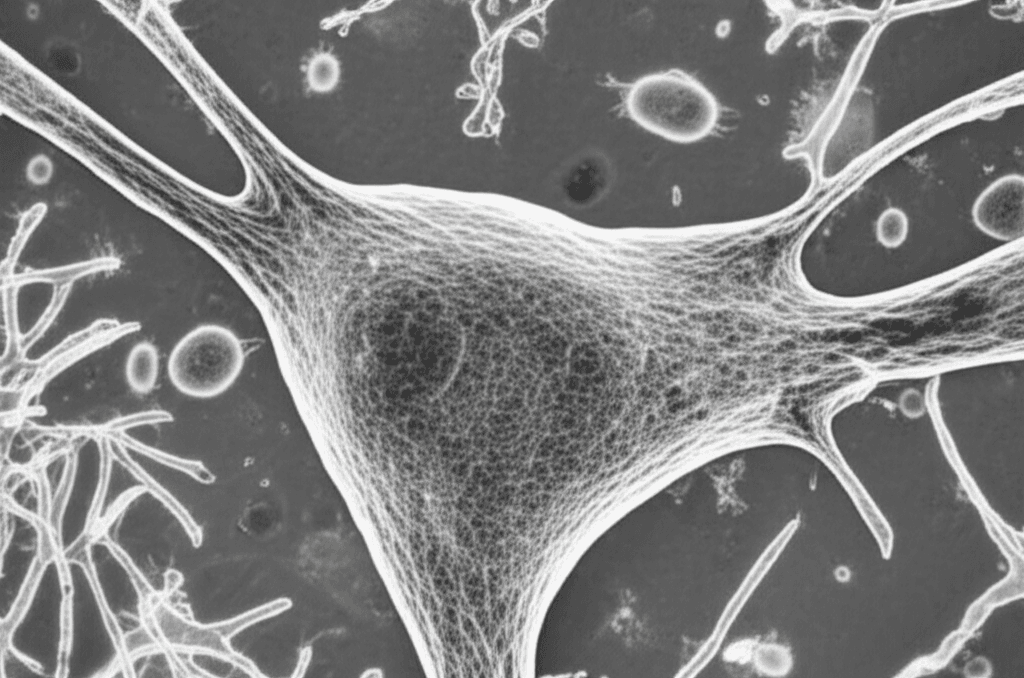

One of the most significant ways exercise combats cancer is by enhancing the body’s immune surveillance. Physical activity can stimulate the mobilization and activity of various immune cells, which are crucial for identifying and destroying abnormal cells, including cancer cells.

- Natural Killer (NK) Cells and Cytotoxic T Cells: Exercise is known to increase the infiltration of immune cells, such as NK cells and cytotoxic T cells, into the tumor microenvironment. These cells are specialized in directly killing cancer cells. A study found that exercise changes the metabolism of cytotoxic T cells, improving their ability to attack cancer cells, and this effect was observed in mice and supported by metabolite changes in human blood samples after intense cycling.

- Cytokine Release: Contracting muscles during exercise release signaling proteins called myokines, such as IL-6, IL-7, and IL-15. These myokines can have direct anti-cancer effects, inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and influencing immune responses and inflammation. Notably, a single workout session can significantly boost myokine production, potentially slowing cancer cell growth by 20-30% in breast cancer survivors. Higher levels of IL-6, in particular, have been linked to a greater reduction in cancer cell growth.

- Reduced Inflammation: Chronic inflammation is a known driver of cancer progression. Exercise helps to reduce systemic inflammation, creating a less supportive environment for cancer to thrive and progress.

Altering Hormonal and Metabolic Environments

Exercise profoundly impacts the body’s metabolic and hormonal balance, which can starve cancer cells or make them more vulnerable to treatment.

- Insulin and IGF-1 Regulation: Physical activity can improve insulin sensitivity and reduce levels of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), specifically IGF-1 and IGF-3. High levels of insulin and IGF-1 are associated with an increased risk of several cancers and can promote cancer cell proliferation and survival. By lowering these factors, exercise can inhibit cancer cell growth pathways.

- Glucose Metabolism: Tumors often rely heavily on glucose for energy (the Warburg effect). High-intensity exercise, in particular, can increase glucose consumption by healthy internal organs, potentially reducing the availability of glucose for tumors to grow and spread. Exercise can also affect cancer metabolism by inhibiting Warburg anaerobic glycolysis.

- Body Composition: Consistent exercise helps reduce fat mass and increase lean muscle mass. Reducing fat mass is crucial because adipose tissue can release pro-inflammatory markers, while improving lean mass helps in producing anti-inflammatory markers, thereby decreasing inflammation that supports cancer progression.

Direct Effects on Tumor Cells and Microenvironment

Beyond systemic changes, exercise can directly influence cancer cells and their immediate surroundings.

- Inhibiting Cell Proliferation and Inducing Apoptosis: Several studies have demonstrated that exercise can directly inhibit cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis (programmed cell death). For instance, serum from individuals after exercise has been shown to decrease the proliferation of triple-negative breast cancer cells and significantly reduce their colony-forming ability in laboratory settings. Moderate-intensity exercise has been particularly highlighted for its ability to inhibit cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in animal studies.

- Improving Tumor Vascularization: Exercise can enhance the density and maturity of blood vessels within tumor tissues, a process known as vascular normalization. This improved blood flow can increase the delivery of oxygen and anti-cancer medicines to tumors, potentially making treatments like chemotherapy more effective.

- Myokine Influence: As mentioned earlier, myokines released during exercise can directly impact tumor biology. Researchers have shown that these muscle-derived proteins can suppress the growth of various cancer cells, including breast cancer cells.

Exercise Recommendations and Considerations for Cancer Patients

Given the growing evidence, exercise is increasingly recommended as an integral part of cancer prevention, treatment, and recovery.

Type and Intensity of Exercise

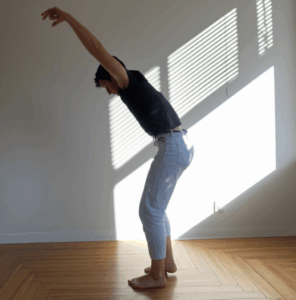

The benefits of exercise vary with type and intensity, though any movement is generally better than none.

- Moderate-Intensity Exercise: Many studies emphasize the protective benefits of moderate-intensity training for inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis. Examples include brisk walking, cycling, or swimming.

- High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) and Resistance Training: Recent research suggests that even a single session of resistance training or HIIT can trigger anti-cancer effects by boosting myokines and suppressing cancer cell growth in breast cancer survivors. HIIT has also shown a negative correlation with pancreatic tumor growth in patients undergoing medical treatment. Strength training, performed at least twice a week, has been linked to a significant reduction in the likelihood of dying from cancer.

- Light-Intensity Activity: Even light-intensity daily physical activity, such as doing errands or household chores, has been associated with a lower risk of cancer. Replacing sedentary time with these activities can reduce cancer risk.

Exercise During and After Cancer Treatment

Exercise is safe and beneficial for most individuals before, during, and after cancer treatment.

- Reducing Side Effects: Physical activity can significantly reduce treatment-related fatigue, anxiety, and depression, and improve quality of life and physical function in cancer patients and survivors. It can also help maintain physical strength, bone health, and range of motion.

- Improving Treatment Efficacy: Exercise may improve tolerance and recovery from surgery. Some preclinical and early-phase clinical studies suggest that exercise can enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy and other cancer therapies, potentially making tumors more responsive to treatment.

- Lowering Recurrence Risk: For survivors of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers, higher levels of physical activity have been associated with a lower risk of cancer recurrence and improved survival.

Important Caveats

While the evidence for exercise’s anti-cancer effects is strong, it’s crucial to acknowledge certain points:

- Not a Direct Cure: While exercise can inhibit cancer cell growth and progression, no studies suggest that it can make malignant tumors disappear entirely. It is considered a complementary part of cancer care, not a standalone cure.

- Individualized Plans: The type and amount of physical activity an individual can handle will depend on their specific cancer type and stage, ongoing treatments, side effects, and current fitness level. Patients should always consult their cancer care team before starting new exercise routines.

- Continued Research: While substantial evidence exists, more targeted clinical and basic research is needed to fully understand the dose-response relationships between physical activity and cancer outcomes, and to establish the precise causal links and mechanisms in human tumor tissues.

Conclusion

The growing body of research unequivocally supports the idea that exercise can reduce cancer cell growth and improve outcomes for cancer patients. By modulating the immune system, optimizing hormonal and metabolic environments, and directly influencing tumor biology, physical activity acts as a potent tool in both cancer prevention and treatment. As scientists continue to unravel the complex molecular mechanisms at play, exercise is increasingly recognized not just as a lifestyle recommendation, but as a critical, evidence-based intervention in comprehensive cancer care, offering a “dose” of cancer-suppressing medicine produced by the body itself.