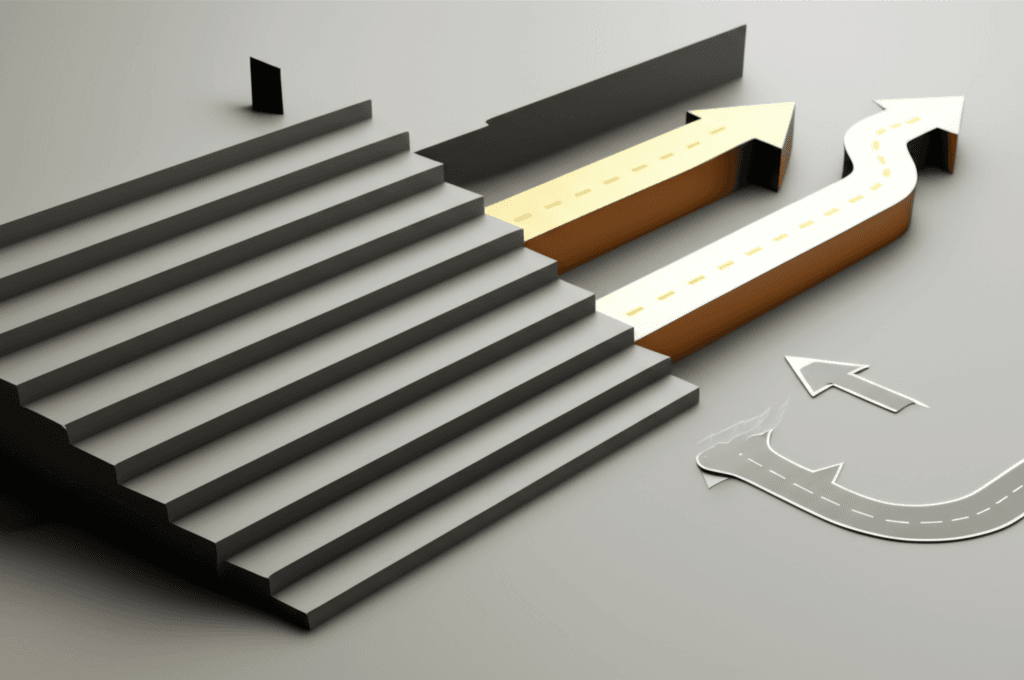

In an ideal society, every individual possesses the chance to improve their life circumstances, regardless of their starting point. This fundamental concept is known as upward mobility, the ability of people to elevate their socioeconomic status. Far from being a mere abstract idea, upward mobility is a cornerstone of a healthy, equitable, and dynamic society, offering a pathway to better jobs, higher incomes, enhanced education, and an improved quality of life.

It signifies more than just financial gain; it encompasses personal growth, self-fulfillment, and the opportunity to build a better future for oneself and one’s loved ones. However, achieving upward mobility is a complex journey, influenced by a myriad of personal, societal, and economic factors that can either propel individuals forward or hold them back.

Defining Upward Mobility: Beyond Income Brackets

Upward mobility refers to the movement of individuals or groups to a higher position within a social hierarchy, typically measured by factors such as income, wealth, education, and occupation. It’s an indicator of a society’s openness and fluidity, reflecting the ease with which individuals can access opportunities that lead to improved living conditions and social standing.

While often discussed in terms of an individual’s career progression, where an employee advances to higher positions with increased compensation and responsibility, upward mobility also has broader societal implications. A high rate of upward mobility often signals a healthy economy and a system that rewards merit, skills, and achievements.

Upward Mobility vs. Social Mobility

Upward mobility is a specific type of social mobility. Social mobility is the broader term, referring to any movement of individuals or groups between different social positions, which can be either upward or downward. When the movement results in an improved socioeconomic class, it is termed upward mobility. Conversely, a decline in socioeconomic status is known as downward mobility.

Types of Upward Mobility

Upward mobility can manifest in various forms, observed both within an individual’s lifetime and across generations.

Intergenerational Mobility

Intergenerational mobility refers to changes in social status between different generations within the same family. For example, if a person’s parents held low-paying jobs but their child becomes a doctor, this represents upward intergenerational mobility. This type of mobility is often used to gauge the level of opportunity and social change present in a society.

Intragenerational Mobility

Intragenerational mobility, on the other hand, describes the change in an individual’s social status over the course of their own lifetime or career. An example would be someone starting as an entry-level employee and, through promotions and skill development, advancing to a managerial position within the same company.

Structural Mobility

Structural mobility occurs when large-scale societal or economic changes cause entire groups of people to move up or down the social ladder, irrespective of individual effort. For instance, a societal shift from an industrial economy to a technology-based one might create new, higher-paying jobs, leading to upward structural mobility for many workers.

Key Factors Influencing Upward Mobility

Numerous interconnected factors contribute to an individual’s or group’s potential for upward mobility.

Education and Skill Development

Education is consistently cited as one of the most significant drivers of upward mobility. Higher levels of education, including college degrees, vocational training, and specialized certifications, generally lead to better job opportunities, higher earnings, and increased career advancement prospects. Access to quality education, from early childhood through postsecondary levels, is a crucial avenue for economic and social advancement.

Economic Conditions and Employment Opportunities

A robust economy with ample job opportunities, particularly well-paying ones, is essential for fostering upward mobility. Economic policies set by governments can significantly impact the availability of these opportunities. Conversely, economic recessions or structural changes in the economy, like deindustrialization, can limit job prospects and hinder social advancement for many. Factors like competitive pay and talent mobility programs within organizations also play a critical role in an employee’s ability to move up.

Family Background and Social Capital

The social status and resources of an individual’s family significantly impact their ability to achieve upward mobility. Children from wealthier families often have access to better schools, tutoring, and valuable social connections, which can provide a considerable advantage. Social capital, which refers to the value of an individual’s social networks and connections, can open doors to educational and professional opportunities. Parental education and occupation are also strong predictors of a child’s upward mobility prospects.

Public Policy and Systemic Factors

Government policies and societal structures play a profound role in shaping upward mobility. These include:

- Housing Stability and Affordability: Stable and affordable housing influences academic achievement, job continuity, emotional health, and the ability to form community ties. Policies that build wealth through home equity can also drive economic mobility.

- Healthcare Access and Well-being: Access to good health care and a healthy environment are essential pillars of support for mobility, as health issues can create significant barriers to employment and education.

- Supportive Neighborhoods: Opportunity-rich and inclusive neighborhoods with lower racial and economic segregation, higher quality schools, and less violent crime promote upward mobility.

- Responsive and Just Governance: Policies that confront and eliminate racial inequities, support community engagement, and provide a safety net are crucial for fostering upward mobility for all.

Challenges to Upward Mobility

Despite the aspiration for widespread upward mobility, significant barriers persist in many societies.

Economic Inequality

High income and wealth inequality can severely limit opportunities for those at the bottom, perpetuating a cycle of poverty. When wealth is concentrated at the top, it can hinder access to quality education and well-paying jobs for marginalized communities.

Systemic Racism and Discrimination

Systemic racism and discrimination are profound obstacles, particularly for marginalized communities. These issues are embedded in various institutions, including the criminal justice system, education, and the labor market, leading to biases in hiring processes, limited access to quality education, and fewer promotion opportunities.

Geographic Disparities

Individuals in economically disadvantaged or rural areas often face limited access to essential resources, including quality schools, good jobs, and social networks, which significantly affects their chances of improving their socioeconomic status. Long commutes due to high housing costs in job centers can also deplete savings and create logistical challenges.

Barriers in Education and Employment

Uneven distribution of access to quality education, with underfunded schools serving disadvantaged populations, creates a disparity in opportunities. Additionally, a lack of well-paying jobs, limited career advancement opportunities, and the prevalence of involuntary part-time work can impede mobility. Other barriers include the cost of childcare, a prior criminal record, and inadequate transportation.

Pathways to Fostering Upward Mobility

Addressing the complex challenges to upward mobility requires a multi-faceted approach involving individuals, organizations, and governments.

Investment in Education and Skill Development

Continued investment in high-quality, accessible education and vocational training programs is paramount. This includes improving school quality in disadvantaged areas, promoting lifelong learning, and equipping individuals with in-demand skills relevant to the evolving job market.

Economic Policies Supporting Equitable Growth

Policies that foster broad-based economic growth, create good jobs with living wages, and reduce income inequality are critical. This can involve progressive taxation, social welfare programs, and initiatives that support small businesses and local economies.

Strengthening Social Safety Nets and Community Support

Robust social safety nets, including affordable housing, accessible healthcare, and childcare support, can provide a foundation for individuals to pursue opportunities. Fostering community support systems and social networks can also provide crucial resources and connections.

Promoting Inclusive Policies and Practices

Actively dismantling systemic barriers like racism and discrimination through policy reform and inclusive practices is essential. This involves ensuring equitable access to housing, employment, and justice, and empowering residents who have experienced poverty and racism to participate in decision-making processes.

Organizational Commitment to Employee Growth

Companies can significantly contribute to upward mobility by offering competitive pay, providing clear career roadmaps, investing in mentorship and training programs, and cultivating a culture that supports professional development and advancement. Recognizing and rewarding merit, skills, and achievements fosters employee motivation and retention.

Conclusion

Upward mobility is more than just an economic concept; it is a measure of a society’s commitment to fairness, opportunity, and human potential. While the journey can be challenging, understanding its various forms, the factors that influence it, and the barriers that impede it, allows for targeted interventions. By investing in education, promoting equitable economic growth, strengthening social support systems, and dismantling systemic inequalities, societies can build more inclusive ladders of opportunity, ensuring that every individual has a genuine chance to climb towards a brighter future.